BurmaBold witnessing amid the chaos of war

Gospel Advance Under the Cover of Chaos

Just months away from celebrating its 10th year free of military dictatorship, Myanmar’s fragile progress toward democracy was crushed. In an overnight coup on Feb. 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military arrested the country’s elected leaders and set up a provisional government. The people of Myanmar, including its growing Christian population, woke to the news that their hopes for lasting freedom had vanished.

Now, two years later, more than 2,800 people have died in the government’s brutal crackdown on mass protests, and more than 16,000 have been arrested for opposing the military government. Myanmar’s economy has collapsed, driving more than half of the population into poverty, which is especially severe in rural areas. As the crisis deepens throughout the country, however, Christian workers see hope — the opportunity to share the gospel in the farthest reaches of Myanmar while the military government is occupied with consolidating its control.

Myanmar, formerly called Burma, is a patchwork of 149 different people groups. While the majority people largely occupy the center of the country, most minority people groups live in rural communities in regions bordering Bangladesh, India, China and Thailand. Ethnic tensions have led to armed conflicts throughout these states, sometimes between the ethnic paramilitaries but mostly — especially since the 2021 coup — between the ethnic paramilitaries and the Myanmar national army.

Living amid this tension and turbulence are Myanmar’s Christians, who, despite being targets of persecution and victims of decades of civil war, remain steadfast in faith. They quietly continue to love their neighbors, reach the lost and carry the word of God into dark and dangerous places.

Once a church decides that they are going to take the Great Commission seriously, then they are going to have conflict.

In the Crosshairs

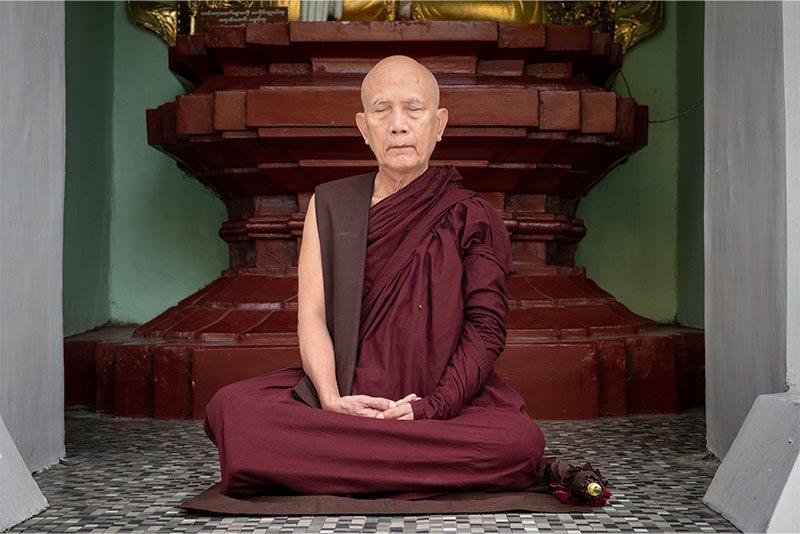

While Myanmar’s constitution promises religious freedom, it also recognizes “the special position of Buddhism as the faith possessed by the great majority of the citizens.” About 8% of Myanmar’s 55 million people are professing Christians, with about 5% identifying as evangelicals. About 78% of the population is Buddhist, with Buddhist monks exercising considerable authority over local education, government, judicial proceedings and the economy. For example, almost all Burmese children are either educated in Buddhist monasteries or in community schools under the oversight of a local monk.

“Once a church decides that they are going to take the Great Commission seriously, then they are going to have conflict, and that conflict will be with either the government or with the Buddhists,” explained a VOM field staff member who has been ministering in Myanmar since 1998.

One front-line worker experienced this kind of conflict firsthand when he was called to a government office and told he couldn’t preach or share the gospel with Buddhists. “I said, ‘In our constitution we have freedom of religion. Is it still the same?’” the worker recalled. “They said, ‘Still the same. You have freedom of religion. You can do any activities in the church compound, but if you do any Christian activities outside of the church compound it is illegal. If you do that you can be arrested and put into prison.’”

He also pointed to the rise of Buddhist nationalism as a concern. “Radical Buddhist monk associations have as their vision and their objective one country, one language, one religion, and they are very, very strong,” he said. While the typical view of Buddhism is that it encourages a peaceful lifestyle, he said these radical associations are about driving out non-Buddhist influence, and they see that the military government is more likely to support this worldview than would be a democratic government.

In rural villages, where a mixture of Buddhism and animism is practiced, Christians are routinely rejected by their families for their faith in Christ. Entire families are expelled from their villages and barred from working the land when they refuse to renounce their faith.

“We had no place to stay,” said Htun, a father of three who lost not only his home but also his small business when his family was expelled from their land because of their Christian faith. “Life was extremely hard, as we struggled even for food and shelter. We had no money, as I lost my job for the sake of our faith in Christ.”

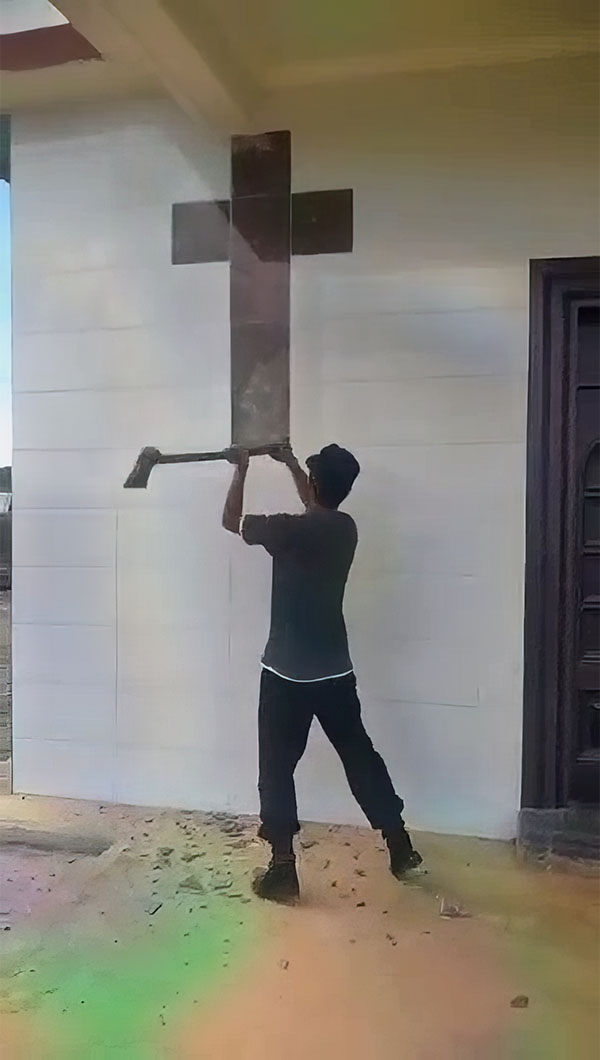

Persecution comes from other sources as well. In 2018, rebels backed by Chinese Communist authorities in the autonomous Wa region of Myanmar’s Shan state detained almost 100 Christian ministers, closed dozens of churches, destroyed several church buildings and threatened believers not to worship even at home. While many nations have sanctioned Myanmar’s military government and limited their relationships with the country, China’s influence has grown economically, technologically and politically. Christian leaders are bracing for more Communist opposition to the faith.

They say there is no place for Christians, that there is no food for Christians.

In the Crossfire

Since the coup, more than 1.2 million people in Myanmar have been displaced by the armed conflicts, forced into refugee camps or makeshift jungle homes as their villages were shelled and homes destroyed. Families flee or send their children to safety as militias round up youth to use as soldiers and couriers.

Many Christians in Myanmar face persecution for their faith even as they suffer the ravages of war. A front-line worker who established a safe house for children said being a Christian in the conflict zones carries a high price. “In the refugee camps, they don’t want to provide for Christian families,” he said. “They say there is no place for Christians, that there is no food for Christians.”

He said that while rebel armies might demand one conscripted soldier from every family in a region, they don’t set limits on conscripts from Christian families. “For Christians, they will take as many children as they want,” he said. “They do it more as a penalty. They think that Christians have betrayed their culture.”

One word sums up life in Myanmar now — uncertainty. “There is uncertainty about the future,” said the VOM field staff member. “No one wants to go back to 15 years ago [before democratic reforms], when it was a very difficult place to live.”

In these times, I don’t know how people would survive in their faith without the Bible.

At a Crossroads

The chaos and upheaval from the coup have created some unexpected opportunities. While the military government has its eyes turned toward its political opposition, evangelists and pastors have quietly entered rural villages, harvest fields and refugee camps to serve people and share the gospel.

Checkpoints have become more common and aggressive, security forces have technology to access data stored on personal electronic devices, and militia and army activity can be unpredictable. But front-line workers don’t allow these increased risks to prevent them from proclaiming the love of Christ.

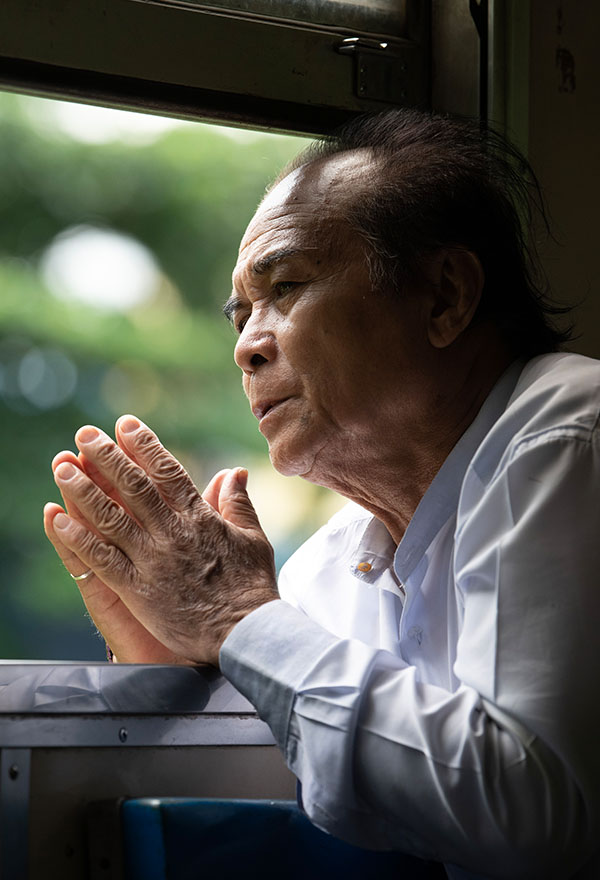

“In spite of all the difficulties, Jesus doesn’t change his pattern and his command,” a front-line worker said. “‘Go’ is still his command, and we still need to go and share the gospel whether we are counted as traitor or not, so we keep doing what we have been doing.”

Supporting those sentiments, the VOM field staff member said, “Now is our opportunity for the gospel, because a time is certainly coming where it will be much more difficult.”

The determination to “go” despite the obstacles is bearing fruit. One evangelist said efforts to win people to Christ are successful even in this season of fear and uncertainty. “I am willing to be persecuted,” he said. “I am not afraid at all, because the gospel we preach is powerful.”

A front-line worker active in Bible distribution said he believes the Lord has been preparing Myanmar for this season of difficulty. During the past few years, VOM has supported the distribution of more than 100,000 Bibles in Myanmar. This has fulfilled a deep need at a time when churches have been restricted from meeting. The front-line worker said most Christian families that he serves have access to at least one Bible in their family or house church. “In these times, I don’t know how people would survive in their faith without the Bible,” he said. “We really praise the Lord [for the recent Bible distribution efforts].”

By continuing to share the gospel and distribute Bibles, front-line workers are shining the light of hope in dark times. “From a political point of view, things seem uncertain,” a front-line worker said, “but one thing we are sure about is Jesus is still our king. Pray Christians in Myanmar will not be disheartened or dismayed, but remain strong in Christ, moving forward in our pilgrimage with joy and boldness.”